“Europe belongs to Picasso, Matisse and many others… India belongs only to me.”

As a woman, I feel as if I am water. I’m an element given to movement, collision, and constant transformation. We are always changing-through the people we meet, our experiences, and life’s challenges.

In 2020, as the world came to a standstill from the pandemic, for the first time in my adult life I felt like I had room to fill myself up. While the world shut down, I focused in. It was as if the sudden elimination of expectation gave me the platform and peace I needed to ground myself for a launch into creative risks.

Over a year later, the world has started to turn back on schedule.

Have you found self-expression difficult as you return to “normal” life? How can we find the foundation to create great art while remaining true to the revelations we made over the lockdown about what we value and what we want to change?

I’m about to show you how an iconic woman from the early 1900s balanced these two tasks.

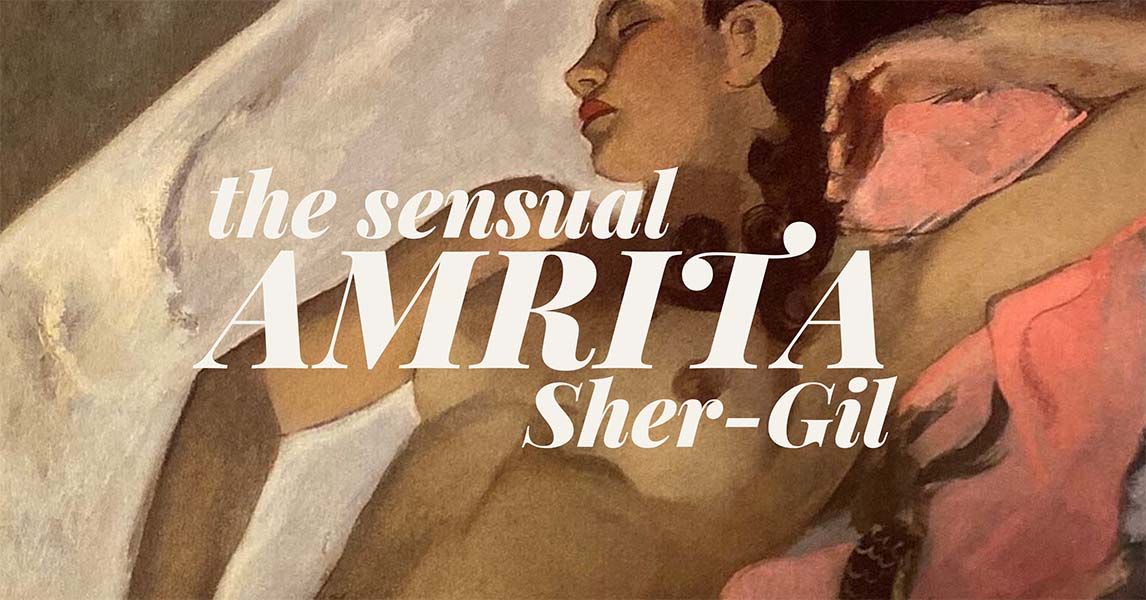

As we look into the New Year, let me introduce you to the sensual Amrita Sher-Gil: India’s most pioneering modern artist.

What can you channel into your own life, both as a creative woman and a soul-driven human being, from Sher-Gil’s short life? Let me fill in a story of a 20th century icon whose story parallels challenges our 21st century lives.

Hungary, Paris, And The Return To One’s Roots

“I think all art, not excluding religious art, has come into being because of sensuality: a sensuality so great that it overflows the boundaries of the mere physical.”

“I think all art, not excluding religious art, has come into being because of sensuality: a sensuality so great that it overflows the boundaries of the mere physical.”

Amrita Sher-Gil was born in Hungary on January 30th, 1913. Her parents are of Hungarian and Sikh descent. Her mother was an opera singer- her father an aristocrat, photographer, and scholar. Sher-Gil lived in Hungary through her childhood years. There, her affluent parents encouraged her natural skills in visual art.

But talent and education alone don’t make an iconic life. Her work wouldn’t blossom into the passionate portfolio we have today until she uncovered her true calling: The Women of India.

But getting back to India? Would first take a detour through Europe’s finest salons.

Sher-Gil, like the young Chavela Vargas, reveled in rebellion. She attended a convent but was expelled at the age of 16 for atheistic beliefs (and insistence on drawing nudes over still life subjects.) Her parents decided Paris would be a better fit for their daughter’s rising career. So they enrolled her in the Ecole Nationale des Beaux-Arts.

Five Years Living In Bohemian Paris

“I stick to my intolerant ideas and my convictions.”

“I stick to my intolerant ideas and my convictions.”

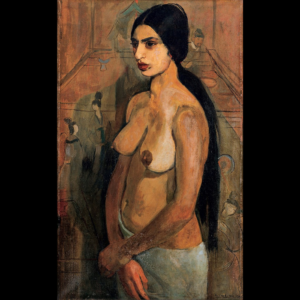

Sher-Gil dove full-force into the thriving bohemian scene of Paris. Her bold, jewel-toned color palette captured sensual portraits of friends, lovers, and- notably- herself. Even still, her intimate self-portraits created deep emotional connection. They draw you into a world both full of wonder and loneliness.

In Paris she discovered how much she enjoyed painting the human figure. Her portraits earned her a place as an associate in the Grand Salon. Sher-Gil had a desire to paint subjects, particularly women, in reality rather than the rapture of religion or as models of the upper class. Influenced by the philosophy of then-celebrity painter Suzanne Valadon, Sher-Gil began to create more controversial pieces.

It was here Sher-Gil found herself caught between two worlds. Her European schooling went head to head with her desire to paint ‘ordinary’ women. Her fierce social presence was at odds with her reclusive creative style.

All of these elements funneled into Sher-Gil like tributaries, producing a profound ocean of work.

But let’s pause for a moment. Here is where, whether she knew it or not, the brilliance of Sher-Gil’s life shines. She funneled everything- her background, her conflict, her talent, etc- into a vibrant creative outcome.

And You Can Do So, Too.

Your influences, goals, obstacles, and desires are not separate containers on a shelf. Instead, they’re droplets from mountain heights and underground springs combining into the essence of who you are.

The problem is…most people don’t see it. They write themselves off as a mud puddle, a mess- rather than an ocean containing great depths and layers of breathing ecosystems.

Amrita Sher-Gil was different. She threw herself into her work and when she emerged? She became a pioneer of the modern art movement.

Sher-Gil Returns to the Land of Tradition

“These little compositions are the expression of my happiness and that is why perhaps I am particularly fond of them.”

“These little compositions are the expression of my happiness and that is why perhaps I am particularly fond of them.”

Amrita Sher-Gil arrived in India at the age of 21 with the desire to focus her work on her Indian heritage.

Her father was heartbroken. He knew India would not accept his bold and beautiful daughter. He asked her not to go. Her mother was pissed. She had hoped her beautiful daughter would seek an aristocratic marriage. But instead Sher-Gil moved to India and married her penniless cousin.

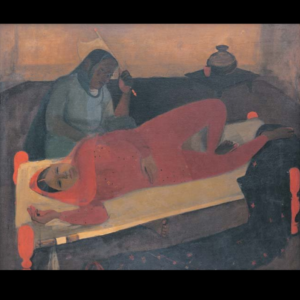

In India she was struck with the lives of working-class women, “feeling in some strange way that there lay my destiny as a painter.” While she had painted female subjects in Paris, it would be these ordinary Indian women and their stories who would be the catalyst of her legacy.

You see, above all Sher-Gil wanted art to feel real. To embody the sensation and electricity of ordinary life. She wanted “to paint those silent images of infinite submission and patience; to depict their angular brown bodies strangely beautiful in their ugliness…”

While Paris focused on the young and the beautiful, Sher-Gil painted the lives around her. She pursued honesty and clarity in her subjects. She brushed off her family’s concerns of what this would mean for her career.

Was Amrita Sher-Gil A Lesbian Artist?

Her close female relationships and intimate portraits brought Sher-Gil’s personal life under scrutiny. According to the New York Times, her own mother questioned whether or not Sher-Gil was a lesbian.

Her close female relationships and intimate portraits brought Sher-Gil’s personal life under scrutiny. According to the New York Times, her own mother questioned whether or not Sher-Gil was a lesbian.

Sher-Gil responded:

“I thought I would start a relationship with a woman when the opportunity arises”

While writing this, Sher-Gil suffered from challenges in her marriage to Victor. Her husband irresponsibly pressured her into dangerous abortions. One abortion of which may have ended her life at the age of 28.

Did she love women sexually? Or did she just fantasize about the freedom female love would have given her in light of her experiences with abortion?

Intolerance towards lesbianism has led many icons throughout history, including perhaps Sher-Gil, to make deep life and career sacrifices to survive. Would Amrita Sher-Gil, given the freedom, chosen to call herself lesbian? Or…something else?

Documentation of Her Intimate Thoughts

Amrita Sher-Gil left a legacy of over 170 documented canvases from her brief life. She also left prolific written documentation of her thoughts and experiences.

She wrote countless letters to Karl Khandalavala, an art critic and fellow intellectual. The two bonded over their mutual love of art. They forged an unusual friendship founded in intellectual kinship. Sher-Gil reveled in her a relationship that gave her freedom of thought without fear of judgement.

Another friend, a female Parisian art critic named Denyse Proutaux, became an intimate confidant.

The concepts of love, relationships, and where to place her affection may have troubled Amrita Sher-Gil. Many self-portraits depict a woman of solitude and loneliness. Her known intimate relationships lead me to wonder what Sher-Gil’s life may have been like in a culture with more fluidity- where modern terms like “demisexuality” may have more closely aligned with Sher-Gil’s true nature.

Refined By History author Heather McConnell speaks (in her review of Portrait Of A Lady On Fire) on love outside of traditional religious or cultural perimeters. Unfortunately, Sher-Gil was never given the opportunity to explore her sexuality. Instead she pushed against norms by putting paint to canvas.

Amrita Sher-Gil’s Final Legacy

“How can one feel the beauty of a form, the intensity or the subtlety of a colour, the quality of a line, unless one is a sensualist of the eyes?”

“How can one feel the beauty of a form, the intensity or the subtlety of a colour, the quality of a line, unless one is a sensualist of the eyes?”

Sexuality aside, Sher-Gil’s paintings breathe sensuality. She expressed a desire to be “an interpreter of the life of the people, particularly the life of the poor and sad.” As she covered women from homely backgrounds, she pulled back the curtain on the unseen detail of the Indian woman’s world.

Sher-Gil’s style changed in her late twenties. She was inspired by Indian miniature paintings. Her portraiture transformed into simplistic and colorful tableaus. Her paintings, and her own life, became blanketed with an overwhelming feeling of resignation. She wrote in a letter, “Little by little I realise that every person carries within herself a calling against which it isn’t hopeless to fight.” In this letter she speaks of motherhood and societal expectations in the face of an accomplished life gone unrecognized without these critical female achievements.

Her writing is melancholy – but not black: “it isn’t hopeless to fight.”

Sher-Gil married and passed too young. This conformity-resisting Aquarius is a cautionary tale for our own desires of love, passion, and artistic expression in the face of cultural pressure.

Finding Your Destiny Between Two Worlds

“There lay my destiny as a painter.”

“There lay my destiny as a painter.”

Post-pandemic, I find myself living between two worlds. In one world, I’ve rediscovered the importance of solitude, gratitude, and focus on my own self. But the pandemic has shown me how critical it is to take public action to guide the path of a changing world.

I often think of how Amrita Sher-Gil would’ve flourished in the world today. Like her, I seek to find pleasure and passion in the present, to shift my focus to things forgotten in a world craving wealth, likes, and attention.

If you would like to learn more about Amrita Sher-Gil I recommend watching this brief documentary, written and narrated by Amrita Sher-Gil’s niece, Navina Sundaram. You can also read a compilation of Sher-Gil’s letters, bound and edited by her nephew, Vivan Sundaram.

With beauty and tenderness,

Lia Flores